Since I spent my teen years in the Eighties of Reagan and AIDS, I’d say that the first thing I made was a mistake. I chalk it up to bad timing. Oh, to be sixteen in 1972 would have been fantastic. That year is emblematic of an era where great innovations and hybridizations were happening the world over in music, and in such incredible proliferation. There were certainly other upheavals too, but man– what was happening with music was truly amazing. Instead, my formative years were spent contemplating the great sexual nadir and skirting the apotheosis of commercial interest in music; favoring instead an underground music that was—despite ample angst and aggression—in retrospect, little more extreme than the vulgate offerings of the day. I have since reconciled the fact that despite my best efforts, I really didn’t have any say in the timing of my birth. What can I say? We move on.

Because my parents are collectors of everything living or otherwise—antique dealers, caretakers of peculiarly fecund animals, and foster parents several times over (our family portrait resembles a Benetton ad from the early nineties), it’s not surprising to have many of one’s early attempts at creation at the ready for presentation and recollection. Their enthusiasm for an increasing liability of too many memories has probably informed my lack of interest in the arms-reach sentimentality of material accrual.

Having recently been back in the Midwest visiting my family, I was afforded the opportunity to visit the museum of my prior enterprises. Mainly for purposes of purging. My brother (22 years younger) was finally departing his childhood home and my parents were vacating this large house for smaller environs. My parents watched, horrified, as I callously opened musty, bug-shorn boxes, assessed a chock-a-block of mementos from the disparate echelons of my seventeen years at home, and then proceeded to dump it all. I live lean. If my environment decreases in size, I purge; if I have less money, I spend less. I aim to be present and future-oriented. I remember what I remember despite the availability of related mementos. These are the things that half the world calls common sense and the other half calls straight-up parsimony.

I unearthed many items from my creative and technical output. Perhaps the oldest was a clay tile the color of a dead lake in winter, glued to a piece of cardboard. Impressed into its surface were rows of dots, the shape of a rabbit, and an assortment of symbols and icons that one might easily find in stamp form, all laid out in some jumble of hieratic sentience that only a child could decipher. There was the puppet from nursery school, a frighteningly bulbous paper maché head with a bird-like protuberance for its nose. The head, whose skin is like rotting leaves in a dried bog, contains one button eye, six strands of vermicious orange yarn for hair that rivals any Jim Henson comb-over, and a barely discernible red crayon mouth. Time has not been good to this little fellow; the back of his head has been bored into by the years and vicissitudes of our atmosphere, revealing the contents of his thoughts—small snatches of language spread across the convolutions of his wrinkled newsprint brain. His noggin is atop a toilet paper roll swathed in rough red fabric and appointed by a frayed, black-and-white striped bow tie knotted in dubious fashion. One fat, lachrymose rivulet of glue wends from his eye and down his face to terminate in various crusty glue spots on his clothing.

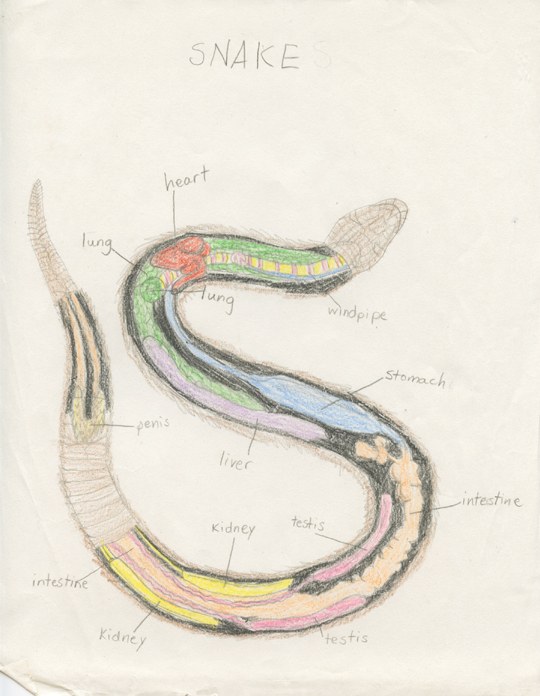

Later, my technical skills improved, and I entered that netherworld of burgeoning identity that is only made worse by the unholy name developed to describe its ungainly awkwardness; I had become a TWEEN. I would fashion wondrous creations with stained glass—swords, dragons and other elements of that world relegated to those with no social options: Dungeons and Dragons. I developed an interest in wood shop and made BBQ forks, a lovely cherry salad bowl (still in use) and a napkin holder. This was at a time when we were becoming dimly aware of the differences in the physiology of boys and girls, and the resultant changes that happen to little ladies. That I might reclaim some of the attention directed toward girls and their needs at the time, I boldly declared that my napkin holder was a Masculine Napkin Holder.

Eventually we became the happy owners of a VHS video camera. With it came, of all things, friends! This took all of our creative endeavors into a group atmosphere as we produced deftly crafted video entertainment. Our music videos, lip-synced to the likes of Prince, Night Ranger, Motley Crüe—replete with drum kits made from Baskin-Robbins ice cream buckets and old political campaign signs for guitars—were, um, well, singular anyway. As were our short films, like the ace bandage-clad slasher classic Summer Vacation (pts I – VII) and the comic-mystery Pink Panther X – where our hapless gumshoe must solve the mystery of the disappearing bandmates of Punk Monk and the Monasteries (soundtrack was the entire “Stay Hungry” record by Twisted Sister).

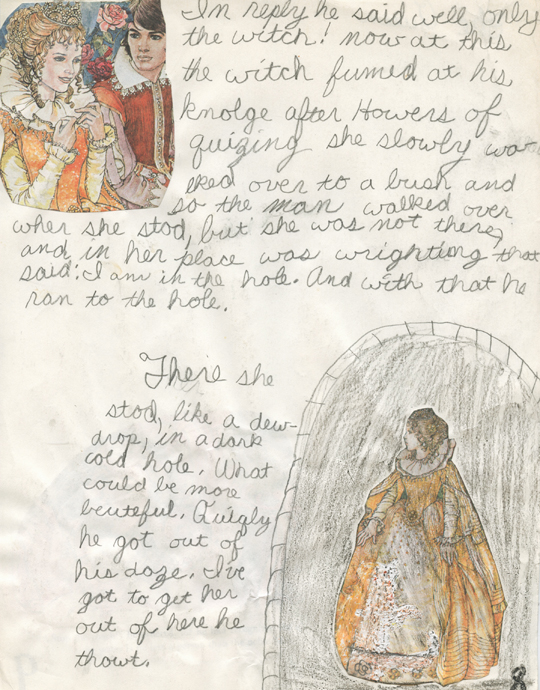

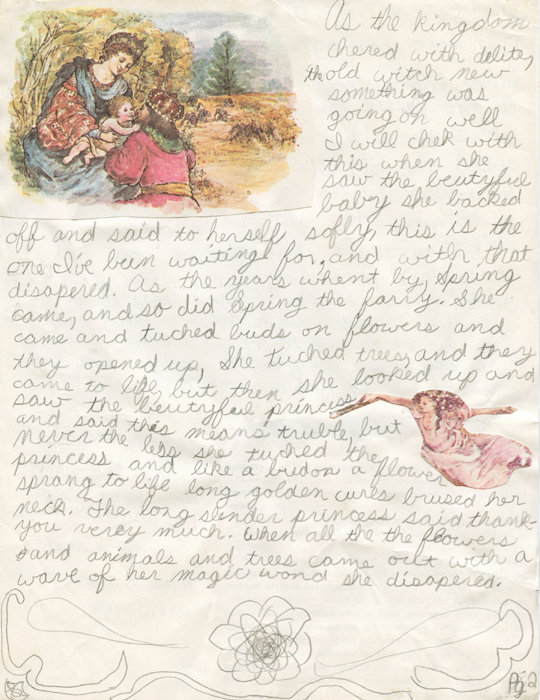

Even auspicious tween dreams are eventually replaced by teen lust. It was time for a new level of social interaction. The D & D and video cam gave way to skateboards, girls and real punk rock. At fifteen and the height of my completely unremarkable skating career, I was struck by a car. Let me be more precise. I was struck by the car I was IN! Let’s just say alcohol was involved and at one point, I immediately exited the vehicle in order to relieve myself. I slid under the car and the back right tire snapped my femur, giving me a leg with the same number of knuckles as my fingers. It was the resulting inability to ambulate that fostered a need for me to really give vent to expression that wasn’t physical. I began to draw. I began to write. I told our pastor that I didn’t believe in God. I began to think and create and give voice to the more cerebral enterprises that I now hold so dear and vital to my existence. The next several years were occupied drawing and writing, which eventually led to my first band and into my first guitar when our original axe-man left the band to become a monk.

Yet, as I delved through all the objects of my creation—the skull-addled everything, the Psychic TV photocopier art, the early and consistent attempts to create something great, but whose most salient attributes were their flaws and the tiny sadness built into them—I didn’t see anything that really had a direct association to who I am and what I do today. That was until I opened my box of stuffed animals.

And that’s what it was. A simple box of old stuffed animals. There was the alligator whose back looked like a pellucid green sea floor, the lion mascot representing the local bank, the Scooby Doo off of which I actually ate most of the hair because at the time I associated it with cotton candy. I didn’t make any of these animals or even modify them in a clever way (with the possible exception of mangy Scooby). But they were key in the creation of something that I rebuild almost every day.

These animals comprised what I called, at two or three years of age, my “contraption.” In the aimless hours of the early single digits, I would select a closet or a tight corner and surround myself up to my neck with my animals. This was my contraption. By being in this compact area packed with stuff, I found a state of grace—perhaps it was love, safety, a return to the surety of the womb, or just a place to feel comfortable with myself and be able to assess the outside world from relative certainty.

This contraption, be it of stuffed animals at the time, would evolve into so many things that were and are critical to my output. It could be the cloistered confines of a studio or the crammed intimacy of a Tokyo venue. Most of my work is in a solo capacity and, over the years, I have built my contraption. I sit, presiding over numerous effect pedals, not only on the floor but on music stands within arm’s reach. I am backed by at least one, but often more, amps of varying sizes. My flanks, which typically would be vulnerable, are bolstered by small tables or stands that hold the sundry objects with which I rend my guitar into anything but. And my guitar, not emblazoned across my ribcage, but tucked comfortably in the crook of my lap, that I might look down upon it, read its total surface, and write its song.

No, it wasn’t the objects that I made. It wasn’t the Zoology club that I started at nine, or the award-winning Pinewood Derby car my dad and I made in Cub Scouts. But rather a state, or space; an environment of transmutable materials, as long as the grace of the state was maintained. To this day, I peer out of my contraption, this locus of creative endeavor, my answer to a claustrophiliac’s prayer. However, I must admit I brought the puppet home because, simply put, it’s fucked.