I’ve titled this "Starting from Scratch: Entrepreneurial Moves in a Contemporary Art Career" because I took what many would say is a non-traditional route to becoming a curator, one which has taught me a lot about being resourceful and professionally proactive. I also spend a lot of time thinking about how I want my career to be, what my best would might look like, and what kind of impact this work could have. This kind of writing helps me organize my non-traditional route into something that appears cohesive. Like I had a plan all along! Which I did not. And, these career questions are all directly related to the importance of striking a delicate balance between controlling my career and allowing for unusual things to happen. This is not an essay about being impractical, but it is about following your instincts and working very, very hard.

So, what was I born to do?

Like most people, I have been working since I was a pre-teen. I have been a tennis instructor, a nanny, a health care researcher, a retail clerk, an ice cream seller, a theater manager, a bartender, a poster putter-upper, an advertising art buyer, a waitress, an opera administrator, a museum front desk ticket seller, and many other roles not worth mentioning.

Thus, I have had many years to think about what working is like, what it can be, what it should not be, and what parts of it I do well. But, more important than all of those, is the question of what I SHOULD be doing. This is not because I think work should be easy, or always fun. (In fact, what I have learned is that what I enjoy is usually not my best skill, something that comes up repeatedly in my life.) And it's not because I don't acknowledge all of the people who have few choices and work wherever and however they can. It's because work that you are driven to do by a deep enjoyment or sense of personal motivation and gratification makes you more productive, more inspiring to those you lead, more aware of opportunities for your organization and, in turn, more successful.

There is somewhat of a pattern, or at least a type, within the jobs I listed above: from a very young age, I was drawn to the arts and went out of my way to incorporate it into my life (did anyone else in my high school take their prom date to the Museum of Fine Arts on their way to the dance? I think not). When I was a wee thing, I saw myself as a Little Orphan Annie-in-waiting, as I dreamed of a Man from Broadway knocking on my door and offering me the starring role. Obviously I was not aware of how Broadway shows are cast, but that mattered not to my young, dreaming self. Later in my schooling, I studied voice and performed with all kinds of musical groups and choruses for many years, including my time in London at Richmond University, when I was a member of the Grosvenor Gilbert & Sullivan Light Opera Company and had a wonderful experience performing with them while being told I did a terrible British accent. (What I heard from backstage after I delivered my line was, "I didn't know Goldie Hawn was in this show!" Hilarious, those Brits.)

There is another element to this that needs mentioning, which is that I had a childhood history of bossiness. This word “bossy” is now being frowned upon as a put-down to young girls, which it totally is—but when I was a child, I was “Bossy” and proud of it. Which really means that I just had lots of ideas and was always looking for someone to execute them with me. Apologies to my younger brother who was the default collaborator on many ideas of which he did not approve. Nevertheless, my experiences at a young age with wanting to lead activities—from directing a little summer camp skit to petitioning for my alternative grade school to host its first school dance (with which we succeeded), to captaining my high school tennis team—were all things I wanted to do with other people. These experiences led to later being ASKED by those in charge to take on leadership roles. This is a good feeling, good for building confidence in a young person, good for gaining experience, really good for learning how to fail (wow, that poetry show I directed for my entire high school was awful), and good for learning how to work with all kinds of people.

My joke nowadays is that if you have something that needs doing in the arts for free, ask Jess and she’ll be suckered into it, but more accurately, this is a reflection of my ongoing desire to make good things happen combined with my affinity for leadership, as I describe above. And you simply don’t always get paid. But, you might get your creative voice heard. And you might meet some great people who become advocates for you later on.

I founded The Project Room in 2011 as the response to all of the things I was driven to do and wanted to become better at. I simply decided that, after seven or so years creating and producing art exhibitions, I wanted to become a better curator. I was concerned about getting locked in a routine of producing exhibitions without rigor, and I found myself spending less time doing things I highly valued like being inquisitive, collaborating with artists, and taking risks. Many years of journal-writing have been dedicated to my career, but on one day I recall in particular, I created two columns in my work journal depicting what I did and did not like about the job of a curator. There were some tasks that were taken for granted as required, like completing a curatorial statement by the opening of an exhibition. Or, what kind of objects could be an in exhibition, what a gallery should be showing, even the way an arts space should look from its level of quietness to the polished completion of the work to the kinds of things that are talked about.

My notebook from 2011 as I worked out the "theme" structure for what is now the foundation of TPR programs

I studied this list and then worked towards only using the columns of things that I liked. Some examples: Regarding that curatorial statement, I replaced it with a “big question," to which the audience, the presenters, other artists, and an online public would respond; the result being a curatorial statement published at the program’s conclusion, closer in likeness to a scientist’s publication of her findings after a laboratory experiment.

My daughter and I in an empty TPR before opening in 2011, thinking about what we should do in there (she was more likely drawing some animals)

Another example is how art is talked about in an arts institution: I decided not to produce lectures or panels, but to host conversations, in which experts would be present to inform the conversation, allowing an audience to contribute and participate in an event that hits a desirable sweet spot between naval-gaze-y and didactic. Creativity was being examined, not art—which meant that I was free to feature start-up entrepreneurs, food writers, radio personalities, and scientists.

While I struggled with questions about what I was meant to be doing, I simply started doing. In a very natural way, then, TPR allowed me to build something and grow it around my creative vision. By making a structure with built-in fluidity and without a pre-existing template, I stuck to my habit of doing what I love to do rather than what is easiest. In other words, I had no arts center to look to for guidance, or materials to draw from—there were bits and pieces of ideas from great places like the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and SITE Santa Fe and others—but this was mostly dreamed up in my head, much like my imaginary casting call for Annie. Another example of doing things the hard way is that I gave birth to my second child one month before TPR opened to the public. This meant that A) I planned the opening programs from my bed during a period of bed rest in my third trimester, during which several kind artists and our web designer met with me at my house, B) I had an infant at my side for the first few months of the endeavor and C) this poor child will never know a TPR-free childhood. Perhaps he will rebel and become an accountant—which, actually, would be really helpful…

Not the enthusiastic expression I was hoping for...

Many people asked me in those early days how I was managing to run a new non-profit arts center with two small children, and I have two different answers, both of which refer to my earlier thesis about what makes success: Answer #1 is “Oh, ha ha, I don’t like to sleep anyway!” and answer #2 is, “Because it’s what I feel I should be doing, what I want to be doing, and that motivates me to work.” There is often a follow-up question, like, “How do you FIND satisfying work in the arts?” To which my obvious answer is, “I have no idea- I had to make myself a job!”

Like most artists—with whom I feel a close affinity—I find it critical to be entrepreneurial, from where funding comes from to how to make a program interesting to how you talk about the organization. Also, like most artists, I think about my work all the time. This allows me to be open to ideas and interesting people. It’s like my good friend the sculptor Dan Webb says: he is always looking at life through his art filter, wondering if whatever it is he is seeing would make for a good sculpture. This is how I think about my work: my day is filled with things that may or may not be good fodder for an arts program or potential funding source. (As an aside, I am a terrible relaxer—each time I have felt truly laid back and free of thoughts, someone has asked me if I am feeling alright. At this point in my life, I am going to assume that it just isn’t a good look for me.) I attribute most of The Project Room's existence and success to my unwillingness to stop thinking about it.

Here is the basic structure of TPR, organized into three platforms:

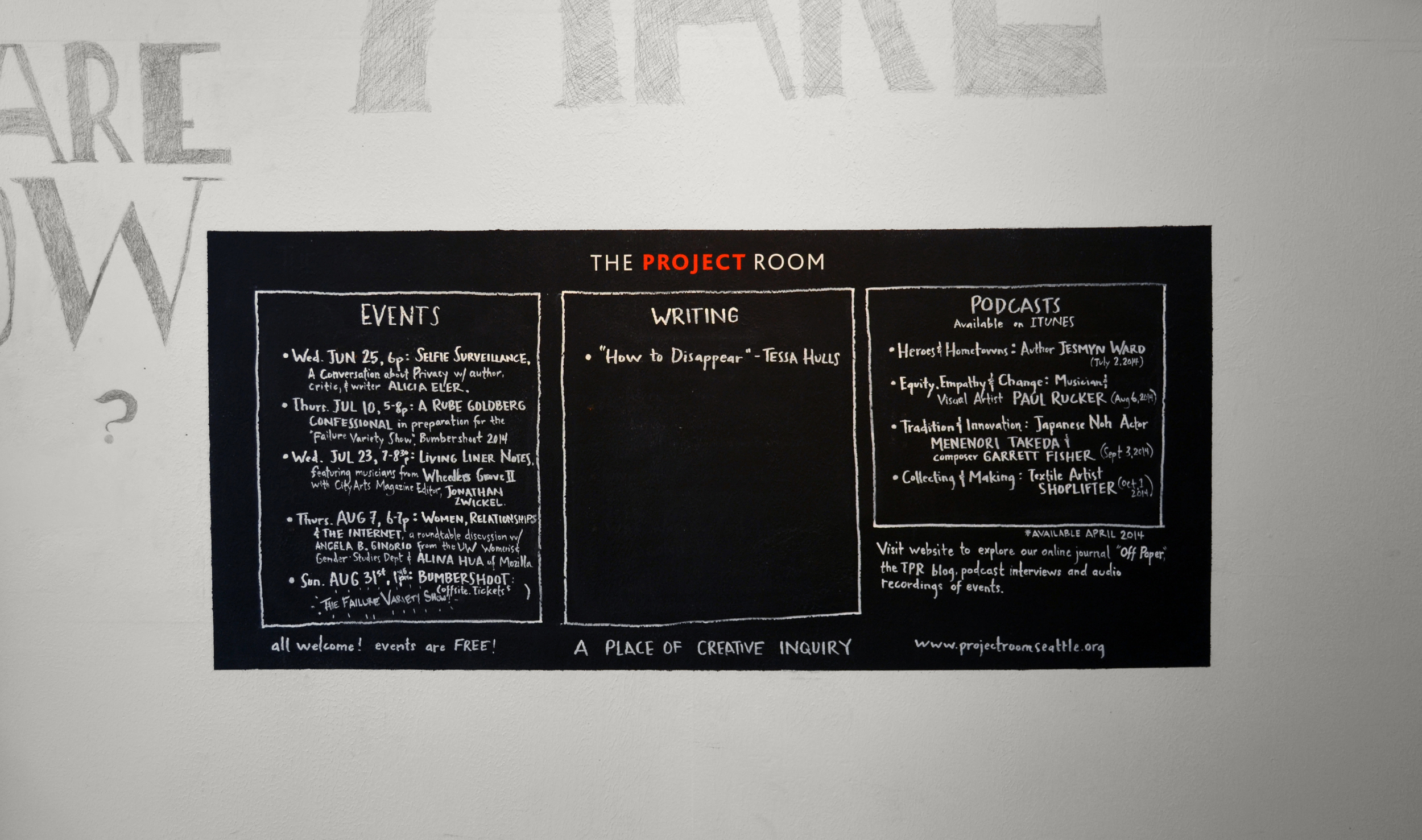

"What is this, a gallery?" * A simple way to explain TPR is to highlight the three main activities we produce: Free public events, an online literary journal (Off Paper), and a podcast interview series. It took me three years to get to this! *Often heard during our first year- thanks to Dan Webb for addressing it in an essay here

And here is how it looks chronologically, using the themes and topics as the common thread that unites each program series:

Our timeline of themes and topics, starting with the "big question" Why Do We Make Things? which had several topics within it, like Authorship and Solutions; and continuing to our current "big question" How Are We Remembered? which is currently hosting the topics "Transformation and Privacy." Think of the topics as book chapters and the big questions as the title of each book.

Here are some visuals which demonstrate how these topic look as specific programs:

TOPIC: Solstenen, a seven-week residency with installation artist Mandy Greer, who set up shop at TPR five days a week and taught visitors how to crochet and be a part of an ongoing project, this topic's namesake. Photo courtesy of The Seattle Times.

One of Mandy's weekly "community crochet parties", which were so popular that return participants began bringing in food to share, thus turning it into a pot-luck-community-crochet-party. Mandy was an outstanding visiting artist and set the tone of inquiry and curiosity that TPR is all about.

TOPIC: Authorship, a series about ownership in creativity, from working collaboratively to repurposing material and interpreting the work of others. Here, musician Stuart Dempster plays on a home-made horn (and other found objects not pictured here) in an program he titled, "Accidents of Manufacture."

TOPIC: Beginnings, a series in which we followed the making of new projects and discussed where and how new ideas take shape. For one year, we followed the making of the play These Streets, from early planning conversations that fueled the script (above), to...

...live performances and events in conjunction with the final and completed staged production at ACT Theatre in Seattle.

TOPIC: Solutions, a series dedicated to creativity as an act of problem-solving. Here, mathematician Steven Strogatz leads a workshop aimed at re-teaching adults how to appreciate math, based on his popular New York Times series on the subject and his book, The Joy of X. (For those of you literary fans: yes, that is the wonderful writer Lesley Hazleton attempting to make a Mobius strip under Steven's supervision.)

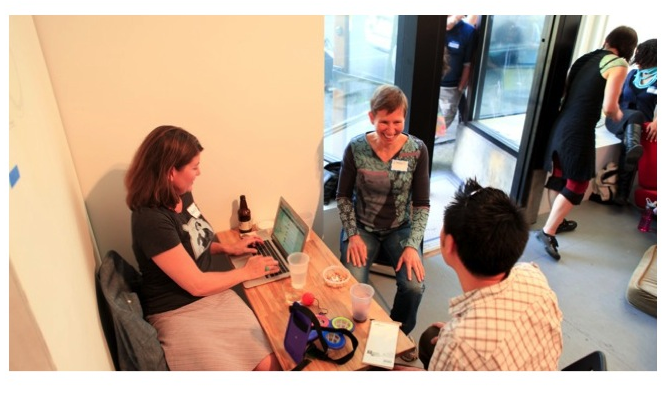

Another program within Solutions was the Art & Technology series, in which artists and technologists got together to meet each other, discuss issues, and make things. Here is the first of three programs, which was a "speed dating"-style event in which everyone was introduced in one-on-one conversations under the guidance of an observant "chaperone".

TOPIC: Failure, our most popular topic thus far, featured a monthly programs called "Successful People Talking About Failure." Sound artist Trimpin (above) was one of the featured presenters.

Another program from Failure was visual artist Veit Stratmann's research into the evacuated Italian town of L'Aquila. Stratmann visited from Paris to share his work, which includes his documentation of the intricate and expensive scaffolding that covers the city but, due to mismanagament of resources, is unable to be removed.

TOPIC: How is Seattle Remembered? This topic began in 2012 as a way to share untold stories from Seattle's past by important figures with deep roots in the city. All the programs are audio recorded and shared online for a public audience. Here, musicians from the 1970s funk scene discuss their memories of Seattle in those days in celebration of the release of the compilation album, Wheedle's Groove Volume II (Light in the Attic Records). From left: Cleve Ticeson, Tony Barton, and Robbie Hill.

Glass pioneer Paul Marioni shared his stories as well, calling his delightful presentation "Sense and Nonsense" for a full house of admirers.

Total Experience Gospel Choir's Patrinell Wright talked about her early days starting the world-renowned choir in a very different Seattle and honored the audience with an impromptu song...

TOPIC: Privacy is one of our current topics, featuring a variety of programs that look into how privacy is related to creativity in today's world. Above, a new online dating app called Siren, created by visual artist Susie J Lee, works with potential users in preparation for its launch.

Another privacy event: A recent workshop about selfies allowed visitors to use vintage Polaroid cameras to create "selfies" based on given instructions, and share them online and on a wall in TPR

And, although I work hard to radiate enthusiasm and positive energy at all times, this is what I often feel like:

The finish line at the women's cross-country skiing race at the 2014 Sochi Olympics. I have been saving this image since I saw the race on TV, thinking it must somehow be useful in thinking about the effort of creativity and entrepreneurship.

And, that’s how I want to feel: like I gave the arts everything I had.